A centuries-old debate about the ethics of future generations may be drawing to a close, but its conclusions raise as many questions as they answer

[This article originally included an anecdote about Derek taking legal ownership of a cat who didn't live with him (in order to be able to truthfully start Reasons and Persons with the line "Like my cat..."), which ended up getting considerably more attention than I anticipated, in part because it seems that nobody else had heard it! Subsequent research by David Edmund's for his forthcoming book about Derek's life, including unearthing the actual ownership 'document', was able to substantiate much of the story but did indicate that some parts of the version I had were incorrect. Since it no longer feels like quite my story to tell, I have decided, therefor, to remove the version contained here (and reprinted elsewhere), at least until the publication of David's book, which I am certainly looking forward to with eager anticipation! In the meantime I might mention my sincere gratitude (not to mention astonishment) to everyone who has helped this little biography get a far wider readership than I ever expected.]

If you have ever studied moral philosophy, and especially utilitarian moral philosophy, chances are that you have come across the ‘Repugnant Conclusion'. This is a commonly cited objection to the view that we should maximise the total amount of happiness in the world. If that were true, the objection runs, then compared with the existence of many people who would all have some very high quality of life, there would be some much larger number of people whose existence would be better, even though these people would all have lives that were barely worth living.

Though seemingly rather innocuous, the Repugnant Conclusion has formed the basis for an increasingly intractable tangle of debates in moral philosophy. Like a mathematical fractal, as philosophers have examined it in greater and greater detail, it has seemed to grow in its complexity, and its repugnance. One widely discussed manuscript on the subject, by the Swedish philosopher Gustaf Arrhenius, considers 400 pages of detailed formal arguments on the subject before concluding that the only way out of this mess is to give up on the idea that we can talk about objective ethical truths at all. Another colleague once told me that, as far as he was concerned, it was the greatest proof ever devised for the non-existence of God!

Yet, despite this, the Repugnant Conclusion has become one of the most popular and famous results of modern moral philosophy. What seems to be much less well known is the story of how it came to be, how philosophers have wrestled with it since and how Derek Parfit, who first came up with the conclusion half a century ago, apparently arrived at a solution shortly before he died on New Year's day, 2017. I want to tell you that story.

“I felt I had been in at the birth of something really important” - Oxford 1968

If you have ever studied moral philosophy, and especially utilitarian moral philosophy, chances are that you have come across the ‘Repugnant Conclusion'. This is a commonly cited objection to the view that we should maximise the total amount of happiness in the world. If that were true, the objection runs, then compared with the existence of many people who would all have some very high quality of life, there would be some much larger number of people whose existence would be better, even though these people would all have lives that were barely worth living.

Though seemingly rather innocuous, the Repugnant Conclusion has formed the basis for an increasingly intractable tangle of debates in moral philosophy. Like a mathematical fractal, as philosophers have examined it in greater and greater detail, it has seemed to grow in its complexity, and its repugnance. One widely discussed manuscript on the subject, by the Swedish philosopher Gustaf Arrhenius, considers 400 pages of detailed formal arguments on the subject before concluding that the only way out of this mess is to give up on the idea that we can talk about objective ethical truths at all. Another colleague once told me that, as far as he was concerned, it was the greatest proof ever devised for the non-existence of God!

Yet, despite this, the Repugnant Conclusion has become one of the most popular and famous results of modern moral philosophy. What seems to be much less well known is the story of how it came to be, how philosophers have wrestled with it since and how Derek Parfit, who first came up with the conclusion half a century ago, apparently arrived at a solution shortly before he died on New Year's day, 2017. I want to tell you that story.

“I felt I had been in at the birth of something really important” - Oxford 1968

|

Derek Parfit was, by all accounts, one of the most brilliant history students of his generation. Having won a scholarship to Eton in 1955, he sailed through the school at the top of every class (except, perhaps, mathematics) before winning another scholarship to Balliol College Oxford. Not only did he excel academically, but he would edit Isis, the leading Oxford student magazine, play Jazz trumpet, write poetry, get involved in student politics and generally be everything a 1960's Oxford student was supposed to be. A close friend, and fellow editor of Isis, Stephen Fry (no, not THAT Stephen Fry) tells of how Derek once dictated a blistering editorial against the hypocrisy of colleges locking out their students at night, having injured himself climbing back into Baliol after a happy evening spent at Somerville. "I mean," he argued, "they put the spikes there a) to stop you climbing in and b) so you can use them as a foothold!"

|

All this was about to change.

Derek's first real taste of failure came when, after graduating with a first in 1964, he was denied a history fellowship at All Souls, Oxford's only college without any students and one of the most prestigious academic institutions in the world. So he went to America, taught himself a new subject and came back, three years later, to successfully retry for a fellowship, this time in Philosophy.

In 1968, the year of the Paris uprising, the assassination of Martin Luther King and the publication of the Population Bomb, Derek worked with two other young philosophers, Jonathan Glover and James Griffin, to establish a new seminar in the Oxford Philosophy department. This aimed, in keeping with the spirit of the times, to consider the application of ethical principles to real-world problems. The original idea was to call it ‘life, happiness and morality.' However, Derek insisted that this wasn't interesting enough and changed its name to ‘death, misery and morality.' It was immensely popular with fellows and students alike.

Jonathan Glover tells the story of what happened next:

"Each week, one of us would speak, and one of us would open the discussion. At the end of one class, the one who would speak next week would hand over their paper to the one who would reply. One week Derek was to speak on a topic, not yet named, and the idea was that I would reply to him. Derek, always polite, made profuse apologies, but he would not be able to hand over the paper – he had a point that was not quite yet settled, but he would send the paper very soon."

After a week of apologetic phone calls, Derek still hadn’t handed over the paper and asked that Jonathan just listen and reply off the cuff. "Not having the faintest idea of what was coming I cheerfully agreed. It was the first outing of the Population Paradoxes and the Repugnant Conclusion. He covered the board with complicated diagrams representing different possible worlds, with named principles and the objections to them. I sat there aghast. It was as though, with no prior knowledge of Quantum Theory, I had gone to some lecture by Niels Bohr and found myself expected to reply to it. I felt I had been in at the birth of something really important, but at the same time had blundered into playing chess with a grandmaster."

While Derek would eventually publish that paper, in 1982, his conviction that he still had ‘a point that was not quite yet settled' would remain...

“A great permanent amelioration of their condition” - London 1798

The Reverend Thomas Malthus was a man with a problem. People’s lustful natures, he believed, were leading them into terrible danger and the world, as he knew it, was coming to an end. Unfortunately for Malthus, while many people, and especially many Christian ministers, had believed this sort of thing for a long time Malthus concluded that these disasters would befall humanity as a result of the laws of nature, rather than the will of God. As he put it:

"The power of population is so superior to the power of the earth to produce subsistence for man, that premature death must, in some shape or other, visit the human race. The vices of mankind are active and able ministers of depopulation. They are the precursors in the great army of destruction, and often finish the dreadful work themselves. But should they fail in this war of extermination, sickly seasons, epidemics, pestilence, and plague advance in terrific array, and sweep off their thousands and tens of thousands. Should success be still incomplete, gigantic inevitable famine stalks in the rear, and with one mighty blow levels the population with the food of the world."

Yes, the Bible did extol Adam and Eve to ‘be fruitful and multiply,' but Malthus was convinced that we should take this commandment with a pinch of salt. It could not be right for people to have children if they had no care for how these children were to live, and what their quality of life would be. Instead, what was needed was to self-consciously limit our reproduction as a species to keep the population size in line with our ability to feed and care for ourselves. Having too many children meant subjecting them "to distress” and squandering the “great permanent amelioration of their condition" that human and technological progress might otherwise bring. If people refused to see this, and to act accordingly, then the state should not step in and save them, or their children, from the ultimate consequences of their actions, since this would only spread the costs to others, encouraging this behaviour and ultimately making the problem worse.

Yet, not all of Malthus's critics were religious. Jeremy Bentham, his contemporary and the founder of modern utilitarianism, believed that population growth was the result of injustice, not of nature. As a utilitarian, Bentham believed that one should seek to maximize the amount of pleasure in the world, and minimize the amount of pain. What is more, he believed that this fact was self-evident and that people only failed to act accordingly because of the conditions in which they lived. Social reforms, such as improving labouring conditions, economic growth, educational provision and criminal justice, would lead to moral reform and allow people to choose what was best.

Bentham was therefore critical of any claim that the poor should be punished for having children by the removal of financial benefits, as Malthus had suggested. Such a policy would not only be unnecessary he believed, but would be actively harmful by increasing the suffering of those who were already burdened by family responsibilities.

Another critic of Malthus’s proposals was the Victorian philosopher John Stuart Mill. Like Bentham, Mill was a utilitarian and opposed the imposition of sanctions on those with large families because this would do them more harm than good. However, Mill spent much more of his time worrying about the effects of population growth and how it kept people in poverty and suffering, unable to fully benefit from the economic growth of his age. His solution was to be an activist for the availability of contraception, something that neither Bentham nor Malthus dared to propose publicly and which lead to his imprisonment at the age of 17.

Mill also famously disagreed with Bentham, whilst partially agreeing with Malthus, on one key point. What should concern utilitarians, he argued, was not the mere quantity of pleasures and pains that individuals experienced, but their overall quality of life. Furthermore, he went on, some pleasures had such “a superiority in quality, so far outweighing quantity as to render it, in comparison, of small account.” This, for Mill, was part of the real benefits that contraception and population control might bring. Not only would it generally reduce the amount of poverty and suffering in the world, but it would also give more people, and especially more women, the opportunity to enjoy a higher quality of life.

However, other utilitarians took a fundamentally different approach. Far from being a mere burden, they argued, population growth would mean more people and hence more happiness. Chief amongst these was Henry Sidgwick, a Cambridge philosopher and late Victorian radical who helped to found Newnham College Cambridge (for the education of women) and the Society of Psychical Research (for the scientific investigation of Christian beliefs). Sidgwick argued that "the point up to which, on utilitarian principles, population ought to be encouraged to increase, is not that at which the average happiness is the greatest possible - as appears to be often assumed by political economists of the school of Malthus - but that at which the happiness reaches its maximum."

Malthus, Bentham, Sidgwick and Mill laid the groundwork for most 20th and 21st century thinking about the ethics of population, and of how we should treat future generations. However, their writings seem to pose a great many more questions than they answer. When we consider population policies, should we focus on the wellbeing of future generations or on how these policies will affect people here and now? And, to the extent that we do care about future generations, should we be concerned about their total sum of happiness or wellbeing, the average wellbeing level of the population as a whole or something else, like each individual's quality of life? These questions would remain largely unaddressed for the next century.

“The limits to growth on this planet will be reached...” Rome (1972)

Throughout his life, Derek Parfit was a passionately perfectionist photographer. There are many stories of him travelling to Venice and St Petersburg (the only places he thought worth photographing) and standing around on some street corner for hours with his camera ready and waiting for just the right light. He would then spend days touching up these photographs at home until he was satisfied that they were as good as possible.

Derek's first real taste of failure came when, after graduating with a first in 1964, he was denied a history fellowship at All Souls, Oxford's only college without any students and one of the most prestigious academic institutions in the world. So he went to America, taught himself a new subject and came back, three years later, to successfully retry for a fellowship, this time in Philosophy.

In 1968, the year of the Paris uprising, the assassination of Martin Luther King and the publication of the Population Bomb, Derek worked with two other young philosophers, Jonathan Glover and James Griffin, to establish a new seminar in the Oxford Philosophy department. This aimed, in keeping with the spirit of the times, to consider the application of ethical principles to real-world problems. The original idea was to call it ‘life, happiness and morality.' However, Derek insisted that this wasn't interesting enough and changed its name to ‘death, misery and morality.' It was immensely popular with fellows and students alike.

Jonathan Glover tells the story of what happened next:

"Each week, one of us would speak, and one of us would open the discussion. At the end of one class, the one who would speak next week would hand over their paper to the one who would reply. One week Derek was to speak on a topic, not yet named, and the idea was that I would reply to him. Derek, always polite, made profuse apologies, but he would not be able to hand over the paper – he had a point that was not quite yet settled, but he would send the paper very soon."

After a week of apologetic phone calls, Derek still hadn’t handed over the paper and asked that Jonathan just listen and reply off the cuff. "Not having the faintest idea of what was coming I cheerfully agreed. It was the first outing of the Population Paradoxes and the Repugnant Conclusion. He covered the board with complicated diagrams representing different possible worlds, with named principles and the objections to them. I sat there aghast. It was as though, with no prior knowledge of Quantum Theory, I had gone to some lecture by Niels Bohr and found myself expected to reply to it. I felt I had been in at the birth of something really important, but at the same time had blundered into playing chess with a grandmaster."

While Derek would eventually publish that paper, in 1982, his conviction that he still had ‘a point that was not quite yet settled' would remain...

“A great permanent amelioration of their condition” - London 1798

The Reverend Thomas Malthus was a man with a problem. People’s lustful natures, he believed, were leading them into terrible danger and the world, as he knew it, was coming to an end. Unfortunately for Malthus, while many people, and especially many Christian ministers, had believed this sort of thing for a long time Malthus concluded that these disasters would befall humanity as a result of the laws of nature, rather than the will of God. As he put it:

"The power of population is so superior to the power of the earth to produce subsistence for man, that premature death must, in some shape or other, visit the human race. The vices of mankind are active and able ministers of depopulation. They are the precursors in the great army of destruction, and often finish the dreadful work themselves. But should they fail in this war of extermination, sickly seasons, epidemics, pestilence, and plague advance in terrific array, and sweep off their thousands and tens of thousands. Should success be still incomplete, gigantic inevitable famine stalks in the rear, and with one mighty blow levels the population with the food of the world."

Yes, the Bible did extol Adam and Eve to ‘be fruitful and multiply,' but Malthus was convinced that we should take this commandment with a pinch of salt. It could not be right for people to have children if they had no care for how these children were to live, and what their quality of life would be. Instead, what was needed was to self-consciously limit our reproduction as a species to keep the population size in line with our ability to feed and care for ourselves. Having too many children meant subjecting them "to distress” and squandering the “great permanent amelioration of their condition" that human and technological progress might otherwise bring. If people refused to see this, and to act accordingly, then the state should not step in and save them, or their children, from the ultimate consequences of their actions, since this would only spread the costs to others, encouraging this behaviour and ultimately making the problem worse.

Yet, not all of Malthus's critics were religious. Jeremy Bentham, his contemporary and the founder of modern utilitarianism, believed that population growth was the result of injustice, not of nature. As a utilitarian, Bentham believed that one should seek to maximize the amount of pleasure in the world, and minimize the amount of pain. What is more, he believed that this fact was self-evident and that people only failed to act accordingly because of the conditions in which they lived. Social reforms, such as improving labouring conditions, economic growth, educational provision and criminal justice, would lead to moral reform and allow people to choose what was best.

Bentham was therefore critical of any claim that the poor should be punished for having children by the removal of financial benefits, as Malthus had suggested. Such a policy would not only be unnecessary he believed, but would be actively harmful by increasing the suffering of those who were already burdened by family responsibilities.

Another critic of Malthus’s proposals was the Victorian philosopher John Stuart Mill. Like Bentham, Mill was a utilitarian and opposed the imposition of sanctions on those with large families because this would do them more harm than good. However, Mill spent much more of his time worrying about the effects of population growth and how it kept people in poverty and suffering, unable to fully benefit from the economic growth of his age. His solution was to be an activist for the availability of contraception, something that neither Bentham nor Malthus dared to propose publicly and which lead to his imprisonment at the age of 17.

Mill also famously disagreed with Bentham, whilst partially agreeing with Malthus, on one key point. What should concern utilitarians, he argued, was not the mere quantity of pleasures and pains that individuals experienced, but their overall quality of life. Furthermore, he went on, some pleasures had such “a superiority in quality, so far outweighing quantity as to render it, in comparison, of small account.” This, for Mill, was part of the real benefits that contraception and population control might bring. Not only would it generally reduce the amount of poverty and suffering in the world, but it would also give more people, and especially more women, the opportunity to enjoy a higher quality of life.

However, other utilitarians took a fundamentally different approach. Far from being a mere burden, they argued, population growth would mean more people and hence more happiness. Chief amongst these was Henry Sidgwick, a Cambridge philosopher and late Victorian radical who helped to found Newnham College Cambridge (for the education of women) and the Society of Psychical Research (for the scientific investigation of Christian beliefs). Sidgwick argued that "the point up to which, on utilitarian principles, population ought to be encouraged to increase, is not that at which the average happiness is the greatest possible - as appears to be often assumed by political economists of the school of Malthus - but that at which the happiness reaches its maximum."

Malthus, Bentham, Sidgwick and Mill laid the groundwork for most 20th and 21st century thinking about the ethics of population, and of how we should treat future generations. However, their writings seem to pose a great many more questions than they answer. When we consider population policies, should we focus on the wellbeing of future generations or on how these policies will affect people here and now? And, to the extent that we do care about future generations, should we be concerned about their total sum of happiness or wellbeing, the average wellbeing level of the population as a whole or something else, like each individual's quality of life? These questions would remain largely unaddressed for the next century.

“The limits to growth on this planet will be reached...” Rome (1972)

Throughout his life, Derek Parfit was a passionately perfectionist photographer. There are many stories of him travelling to Venice and St Petersburg (the only places he thought worth photographing) and standing around on some street corner for hours with his camera ready and waiting for just the right light. He would then spend days touching up these photographs at home until he was satisfied that they were as good as possible.

|

Yet, for him, the best photograph ever taken was one that was taken on the fly and in far from perfect conditions. ‘Earthrise' was snapped by Bill Anders aboard the Apollo 8 moon orbiter on Christmas Eve 1968. "Oh my God!" Anders was recording saying "Look at that picture over there ... hand me that roll of colour quick, would you."

Parfit argued that this photograph was best because it gives everyone who sees it the sense that we are there, floating in space far from the place we call home. This could not be explained only by the image itself, no mere artist’s impression however accurate or compelling, would have been so worthwhile. It is said that Earthrise divides the earth’s population into two groups, those who were already alive before it was taken, and who can remember seeing it for the first time, and those who have grown up in a world where there this photograph already exists. It changed the world. |

One of the things that resulted from the publication of Earthrise was a renewal in thinking about the problems described by Malthus. In the 30 years following the Second World War the combination of the demographic Baby Boom and the post-war Economic Miracle lead to a huge increase in the size of humanity’s impact on the planet with some pollutants increasing by 900%. Faced with the reality of a single finite planet floating in a black abyss, the unsustainability of this trend began to hit home. This helped to turbocharge the nascent environmental movement of the time and radically altered people's notions of what it meant to live an ethical life.

This new thinking reached its zenith in 1972 with the publication of the influential report ‘Limits to Growth' by the Club of Rome. Its conclusions were stark "If the present growth trends in world population, industrialization, pollution, food production, and resource depletion continue unchanged, the limits to growth on this planet will be reached sometime within the next one hundred years." As it happened, global population growth had peaked at 2% per year in the late 1960s, while the years of high economic growth were almost at an end. However, for a time at least the need for a coherent global population policy seemed extremely urgent. All of a sudden the 19th century's unanswered questions about how we would treat future generations felt a lot more urgent.

Two of the first philosophers to take up this challenge were Jan Narveson and Peter Singer. Both were deeply unconvinced by Sidgwick's argument that we should have more children because these would increase the overall sum of happiness, even if this meant each individual was worse off. For Narveson, this was conclusive proof that utilitarians were getting something badly wrong in how they viewed the world. We should not care about people because they might experience happiness, he argued, rather we should only care about happiness because it is, in fact, good for people. This he summarized in his infamous philosophical slogan ‘we are in favour of making people happy, but neutral about making happy people'.

Singer, who was to become one of the most influential, if controversial, philosophers of our times, did not quite share this view though he also rejected Sidgwick's conclusion. For him, it was vital that humanity continued, but not that the population of humans grew any larger. His initial proposal was that we should seek to divide future generations into two separate groups, consisting of those people “who would exist anyway, i.e. independently of whatever choice or policy was under consideration” and those “whose existence would be contingent upon our actions.” We should then treat this ‘core' of people whose existence was guaranteed in the same way that we might treat anyone who already exists, and should promote their welfare as much as possible. However, we should care much less about those whose existence depended on our actions and should not be concerned if we caused them never to be born, so long as this was in the interest of everyone else.

For Derek however, both of these views were incorrect. While he raised many complex objections against both of them, one that he continually returned to is that sometimes a person's life may be so full of suffering and other bad things that we would be forced to accept that this person was harmed by coming into existence. Given that this is so, it would be wrong to overlook the value of these people's lives, even if they are in the far future or if their existence depended on our actions. Hence, neither Singer nor Narveson give us excuses for ignoring the harm we might bring to future people, even if it is sometimes compelling to believe that we do not need to worry about the benefits we might give them instead.

However, he went on to argue, if we only considered the harms we brought to future generations this would have highly counterintuitive results. For instance, it would imply that, even if we believed it was good that the world exists with its current population, because whilst some people suffer most people's lives are worth living, it could be wrong for us to have children who would live in a world that was like our own, or even much better, because that future world might still contain some suffering. Derek labelled this an ‘Absurd Conclusion'.

While there is more than one way to avoid this conclusion, he argued that the route we should take is to accept, right from the start, that every life that is worth living must be in some way good and make the universe better for its existence. He called this the ‘Simple View'. This view was nothing like a strong as Sidgwick's utilitarianism. However, Parfit realized that it would still face significant problems of its own.

“...this would be very hard to accept” Oxford (1984)

"Like my cat, I often simply do what I want to do." This was the opening sentence of Derek Parfit's philosophical masterpiece, Reasons and Persons. He believed that it was the best way to begin his book because it showed something important about people. Often we are not as special as we think we are. For instance, when people simply do what they want to do they appear to be utilizing no ability that only people have. On the other hand, when we respond to reasons, we are doing something uniquely human, because only people can act in this way. Cats are notorious for doing what they want to do, and the sense of proximity between a cat and its owner pleasingly heightens our sense of their similarity. Hence, there could be no better way for this book to begin.

Reasons and Persons was far from being Derek's final word on the philosophical problems that had consumed him for the previous 17 years. Indeed, it has been said that Derek only agreed to publish it under pressure from All Souls College who were threatening not to renew his fellowship, and he insisted the publisher accept it in 154 individual instalments so that he could submit each one at the last possible moment, mere days before the book went to press. Yet, the book has become one of the most influential, and heavily cited, works of philosophy published since the Second World War. It consists of four sections, each of which considers a different set of arguments for why people matter less than we might suppose, and why our reasons for action might be otherwise than they seem.

In the first part, Derek corrects what he sees as some important errors in moral mathematics. For instance, he spends considerable time showing how individuals can be said to make a significant moral difference, even when they are only working as part of a much larger group and would achieve nothing on their own. More importantly, he begins a long argument, which he would continue in his later work, to the effect that many apparently large differences between ethical theories are much less deep than commonly assumed. For instance, some moral theories claim that people have special duties to help their own children, even to the detriment of the children of others. However, he argued, because everyone's children would expect to benefit if parents were more concerned about the wellbeing of children in general, rather than always prioritizing their own children even if they could do more to help other people's, such theories were ‘collectively self-defeating' if strictly interpreted, and should instead be revised to make them more utilitarian.

In the second part, Derek attacked the notion that one had decisive reasons to place one's own, long run, self-interest over the wellbeing of others. He did this by proposing a third possible position one might take, recklessly seeking present pleasures at the expense of one's long-run self-interest. Whilst accepting that all three positions might be, in some sense, rational, Derek conclusively showed how any argument for why one should be concerned with what would make one’s life go best overall, rather than merely right now, could be turned to imply that one should instead be concerned with everyone’s wellbeing, not just one’s own.

In the third Part, Derek moved on to the concept of what constitutes a person, and in particular what makes someone the same person today, tomorrow and for their whole life. He showed how while our concept of what it means to be a person is adequate for dealing with ordinary, everyday cases, there were other cases, which are not hard to imagine and that may well occur one day, in which it breaks down. For instance, if people underwent the total separation of their two brain hemispheres or were replicated by a Star Trek style matter transporter into two separate individuals in different locations, who both believed themselves to be the original person. Other philosophers have devised sophisticated theories about personhood that tell us how we should react to these cases. However, Derek argued that our concept of a person simply cannot deal with them at all. He thus concluded that personhood is a ‘reductive' concept that, whilst tracking certain physical and psychological facts about an individual over time, implies no substantial further fact about the world.

This new thinking reached its zenith in 1972 with the publication of the influential report ‘Limits to Growth' by the Club of Rome. Its conclusions were stark "If the present growth trends in world population, industrialization, pollution, food production, and resource depletion continue unchanged, the limits to growth on this planet will be reached sometime within the next one hundred years." As it happened, global population growth had peaked at 2% per year in the late 1960s, while the years of high economic growth were almost at an end. However, for a time at least the need for a coherent global population policy seemed extremely urgent. All of a sudden the 19th century's unanswered questions about how we would treat future generations felt a lot more urgent.

Two of the first philosophers to take up this challenge were Jan Narveson and Peter Singer. Both were deeply unconvinced by Sidgwick's argument that we should have more children because these would increase the overall sum of happiness, even if this meant each individual was worse off. For Narveson, this was conclusive proof that utilitarians were getting something badly wrong in how they viewed the world. We should not care about people because they might experience happiness, he argued, rather we should only care about happiness because it is, in fact, good for people. This he summarized in his infamous philosophical slogan ‘we are in favour of making people happy, but neutral about making happy people'.

Singer, who was to become one of the most influential, if controversial, philosophers of our times, did not quite share this view though he also rejected Sidgwick's conclusion. For him, it was vital that humanity continued, but not that the population of humans grew any larger. His initial proposal was that we should seek to divide future generations into two separate groups, consisting of those people “who would exist anyway, i.e. independently of whatever choice or policy was under consideration” and those “whose existence would be contingent upon our actions.” We should then treat this ‘core' of people whose existence was guaranteed in the same way that we might treat anyone who already exists, and should promote their welfare as much as possible. However, we should care much less about those whose existence depended on our actions and should not be concerned if we caused them never to be born, so long as this was in the interest of everyone else.

For Derek however, both of these views were incorrect. While he raised many complex objections against both of them, one that he continually returned to is that sometimes a person's life may be so full of suffering and other bad things that we would be forced to accept that this person was harmed by coming into existence. Given that this is so, it would be wrong to overlook the value of these people's lives, even if they are in the far future or if their existence depended on our actions. Hence, neither Singer nor Narveson give us excuses for ignoring the harm we might bring to future people, even if it is sometimes compelling to believe that we do not need to worry about the benefits we might give them instead.

However, he went on to argue, if we only considered the harms we brought to future generations this would have highly counterintuitive results. For instance, it would imply that, even if we believed it was good that the world exists with its current population, because whilst some people suffer most people's lives are worth living, it could be wrong for us to have children who would live in a world that was like our own, or even much better, because that future world might still contain some suffering. Derek labelled this an ‘Absurd Conclusion'.

While there is more than one way to avoid this conclusion, he argued that the route we should take is to accept, right from the start, that every life that is worth living must be in some way good and make the universe better for its existence. He called this the ‘Simple View'. This view was nothing like a strong as Sidgwick's utilitarianism. However, Parfit realized that it would still face significant problems of its own.

“...this would be very hard to accept” Oxford (1984)

"Like my cat, I often simply do what I want to do." This was the opening sentence of Derek Parfit's philosophical masterpiece, Reasons and Persons. He believed that it was the best way to begin his book because it showed something important about people. Often we are not as special as we think we are. For instance, when people simply do what they want to do they appear to be utilizing no ability that only people have. On the other hand, when we respond to reasons, we are doing something uniquely human, because only people can act in this way. Cats are notorious for doing what they want to do, and the sense of proximity between a cat and its owner pleasingly heightens our sense of their similarity. Hence, there could be no better way for this book to begin.

Reasons and Persons was far from being Derek's final word on the philosophical problems that had consumed him for the previous 17 years. Indeed, it has been said that Derek only agreed to publish it under pressure from All Souls College who were threatening not to renew his fellowship, and he insisted the publisher accept it in 154 individual instalments so that he could submit each one at the last possible moment, mere days before the book went to press. Yet, the book has become one of the most influential, and heavily cited, works of philosophy published since the Second World War. It consists of four sections, each of which considers a different set of arguments for why people matter less than we might suppose, and why our reasons for action might be otherwise than they seem.

In the first part, Derek corrects what he sees as some important errors in moral mathematics. For instance, he spends considerable time showing how individuals can be said to make a significant moral difference, even when they are only working as part of a much larger group and would achieve nothing on their own. More importantly, he begins a long argument, which he would continue in his later work, to the effect that many apparently large differences between ethical theories are much less deep than commonly assumed. For instance, some moral theories claim that people have special duties to help their own children, even to the detriment of the children of others. However, he argued, because everyone's children would expect to benefit if parents were more concerned about the wellbeing of children in general, rather than always prioritizing their own children even if they could do more to help other people's, such theories were ‘collectively self-defeating' if strictly interpreted, and should instead be revised to make them more utilitarian.

In the second part, Derek attacked the notion that one had decisive reasons to place one's own, long run, self-interest over the wellbeing of others. He did this by proposing a third possible position one might take, recklessly seeking present pleasures at the expense of one's long-run self-interest. Whilst accepting that all three positions might be, in some sense, rational, Derek conclusively showed how any argument for why one should be concerned with what would make one’s life go best overall, rather than merely right now, could be turned to imply that one should instead be concerned with everyone’s wellbeing, not just one’s own.

In the third Part, Derek moved on to the concept of what constitutes a person, and in particular what makes someone the same person today, tomorrow and for their whole life. He showed how while our concept of what it means to be a person is adequate for dealing with ordinary, everyday cases, there were other cases, which are not hard to imagine and that may well occur one day, in which it breaks down. For instance, if people underwent the total separation of their two brain hemispheres or were replicated by a Star Trek style matter transporter into two separate individuals in different locations, who both believed themselves to be the original person. Other philosophers have devised sophisticated theories about personhood that tell us how we should react to these cases. However, Derek argued that our concept of a person simply cannot deal with them at all. He thus concluded that personhood is a ‘reductive' concept that, whilst tracking certain physical and psychological facts about an individual over time, implies no substantial further fact about the world.

|

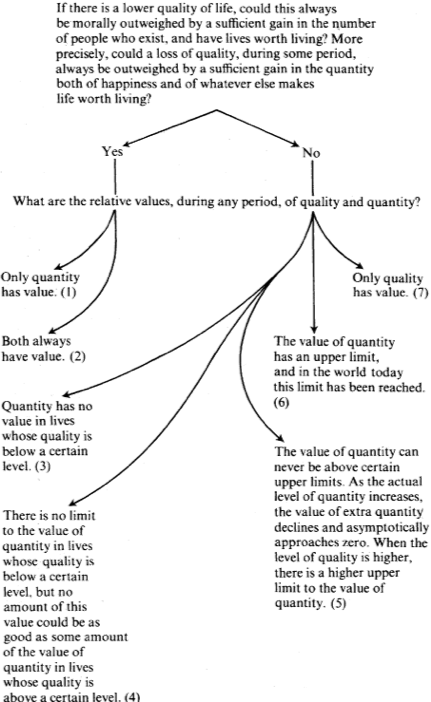

In the final part, Derek tackled the problem of how we should ethically think about future generations of people, and deal with the problems of population ethics. Of all the wild and ambitious arguments in Reasons and Persons, this section has proven the most controversial. On consideration, Parfit concludes that one must reject the view suggested by Henry Sidgwick about what a utilitarian should do - i.e. seek to maximise the total quantity of future happiness. This view, he argued, would imply the Repugnant Conclusion, that enough people who each had a life ‘barely worth living' would be ethically better than some very large number of people who each enjoyed a very high quality of life, and ‘this would be very hard to accept'. Even if we had to accept that this was, collectively, better for all the people who would exist with lives worth living, it would still be a worse outcome, because these people would have a much lower Quality of Life.

However, Derek also realized that this was not the end of the story because Sidgwick's utilitarian argument was not the only chain of reasoning that lead to this Repugnant Conclusion. Furthermore, all the other views one might hold, though they might not imply the Repugnant Conclusion, had their own problematic conclusions (including the Absurd Conclusion, which I mentioned earlier, the Sadistic Conclusion, the Ridiculous Conclusion and the Elitist Conclusion). |

The many technical arguments of this part of the book are hard to summarize - so I will consider just one. A common first move people are tempted to take upon learning about the Repugnant Conclusion is to take the view Sidgwick (probably falsely) attributed to Malthus, according to which it is not the total quantity of wellbeing that we are trying to maximize but rather the average level of wellbeing of people in general. Parfit suggested many counter arguments to this view; however, his most convincing invited the reader to consider two possible worlds, Hell 1 and Hell 2. In Hell 1, very many people all live lives of unendurable suffering, yet they are forced to endure it for many years. They experience no pleasure or other good things, and their lives are full of pain. If any lives are ‘not worth living' it is surely these. In Hell 2, these same people will all live and have lives that are even worse, for instance, they will be just as bad but twice as long. Many other people will also live in this world and their lives will be very nearly, but not quite, as bad as that of the people in Hell 1. They will still suffer, but their agony will be slightly less. If there are enough of these people in Hell 2, then the average wellbeing level of the population will be slightly higher than in Hell 1, but surely we would not take the view that Hell 2 is, therefore, better than Hell 1? Clearly, it is worse.

Eventually, Parfit came to the conclusion that the best way of avoiding the Repugnant Conclusion would be to revive the argument put forward by John Stuart Mill, that some changes in a person's ‘Quality of Life' might be so important that they would render any change in the mere quantity of wellbeing in the world morally insignificant. In 1986 Derek published a paper proposing this view, which he called ‘Perfectionism', but at the same time concluding that it was ‘crazy'. He would not publish anything more about his Repugnant Conclusion for another 30 years.

“But this ... would be only one of our beliefs” Oxford (2017)

As the years passed, Derek Parfit's philosophical inquiries became his obsessions, and gradually drove out all of the other interests of that brilliant young student of the 1960's. By the time Reasons and Persons was published, he seemed to do nothing except philosophy and photography. In his own words, he had become a duomaniac. After publishing Reasons and Persons he met his future wife Janet and bought what he felt was the perfect house, deep in the wilds of Wiltshire, before promptly returning to his duomania and spending his time either in his study or abroad, teaching and taking photographs. Gradually a legend built up around him. ‘Derek only eats meals he can consume with one hand so he can read and eat at the same time'. ‘’Derek drinks instant coffee made with hot water from the tap, so he doesn't have to wait for the kettle to boil'. ‘Derek always wears the same clothes, even in the St Petersburg winter, to spare him from having to think about what to put on in the morning'. Unusually for such legends, this was all completely true.

Eventually, he would become a monomaniac; devoting his entire life to philosophical problems and nothing else.

One of the problems that concerned him greatly was the ‘non-identity problem'. As we have already seen, Derek believed that future people mattered a great deal and that any future person's life would make the world better if their life was ‘worth living', to say otherwise would be absurd. He also believed that it would be better if future people lived better lives, and worse if they lived worse lives. However, he could not get rid of the nagging doubt that this view was more problematic than it might, at first, seem.

To appreciate this, we need to realise just how unique everyone is. I am not simply ‘Simon Beard' or ‘My parents' second son', I am an individual who is defined, at the very least, by a complex genetic code and a precise set of environmental conditions. These were themselves determined by a wide range of circumstances, not only who my parents were but the precise time and manner in which they conceived me, not only the exact sperm and egg the fused at that time, but the complex process by which the genetic material from each interacted in producing my own, unique, genetic code. Had any of these things been other than they were, I would never have existed.

This is a problem because it follows that somebody contemplating an act or choice that might affect ‘me' may also have some influence upon the conditions in which I come into being, and hence who I am. If they do, then their choices cannot be said to benefit, or harm, me, because had they acted differently then I would not have existed. However, if that is so, and philosophers generally agree that it is, then why should they be concerned about my welfare at all? Yes, they affect whether I exist at all, but even that cannot be said to benefit me, because had I not existed, then there would be no me who was harmed by this.

It is natural to assume that when we say things like ‘anyone's life is good, and makes the world better, if that person's life is 'worth living' then this is good because it benefits the person who gets to live that good life. However, the non-identity problem suggests that this is not so. Either we must say that the lives of future people do not matter, or we must say that they are good, but not because they benefit the people who live them. For most of his life, Derek believed that we must say the latter. He labelled this the ‘No Difference View' because it implied that it made no difference whether a person is actually benefited by living a good life or not, but only that this good life exists. However, he was deeply dissatisfied by this conclusion.

Eventually, Parfit came to the conclusion that the best way of avoiding the Repugnant Conclusion would be to revive the argument put forward by John Stuart Mill, that some changes in a person's ‘Quality of Life' might be so important that they would render any change in the mere quantity of wellbeing in the world morally insignificant. In 1986 Derek published a paper proposing this view, which he called ‘Perfectionism', but at the same time concluding that it was ‘crazy'. He would not publish anything more about his Repugnant Conclusion for another 30 years.

“But this ... would be only one of our beliefs” Oxford (2017)

As the years passed, Derek Parfit's philosophical inquiries became his obsessions, and gradually drove out all of the other interests of that brilliant young student of the 1960's. By the time Reasons and Persons was published, he seemed to do nothing except philosophy and photography. In his own words, he had become a duomaniac. After publishing Reasons and Persons he met his future wife Janet and bought what he felt was the perfect house, deep in the wilds of Wiltshire, before promptly returning to his duomania and spending his time either in his study or abroad, teaching and taking photographs. Gradually a legend built up around him. ‘Derek only eats meals he can consume with one hand so he can read and eat at the same time'. ‘’Derek drinks instant coffee made with hot water from the tap, so he doesn't have to wait for the kettle to boil'. ‘Derek always wears the same clothes, even in the St Petersburg winter, to spare him from having to think about what to put on in the morning'. Unusually for such legends, this was all completely true.

Eventually, he would become a monomaniac; devoting his entire life to philosophical problems and nothing else.

One of the problems that concerned him greatly was the ‘non-identity problem'. As we have already seen, Derek believed that future people mattered a great deal and that any future person's life would make the world better if their life was ‘worth living', to say otherwise would be absurd. He also believed that it would be better if future people lived better lives, and worse if they lived worse lives. However, he could not get rid of the nagging doubt that this view was more problematic than it might, at first, seem.

To appreciate this, we need to realise just how unique everyone is. I am not simply ‘Simon Beard' or ‘My parents' second son', I am an individual who is defined, at the very least, by a complex genetic code and a precise set of environmental conditions. These were themselves determined by a wide range of circumstances, not only who my parents were but the precise time and manner in which they conceived me, not only the exact sperm and egg the fused at that time, but the complex process by which the genetic material from each interacted in producing my own, unique, genetic code. Had any of these things been other than they were, I would never have existed.

This is a problem because it follows that somebody contemplating an act or choice that might affect ‘me' may also have some influence upon the conditions in which I come into being, and hence who I am. If they do, then their choices cannot be said to benefit, or harm, me, because had they acted differently then I would not have existed. However, if that is so, and philosophers generally agree that it is, then why should they be concerned about my welfare at all? Yes, they affect whether I exist at all, but even that cannot be said to benefit me, because had I not existed, then there would be no me who was harmed by this.

It is natural to assume that when we say things like ‘anyone's life is good, and makes the world better, if that person's life is 'worth living' then this is good because it benefits the person who gets to live that good life. However, the non-identity problem suggests that this is not so. Either we must say that the lives of future people do not matter, or we must say that they are good, but not because they benefit the people who live them. For most of his life, Derek believed that we must say the latter. He labelled this the ‘No Difference View' because it implied that it made no difference whether a person is actually benefited by living a good life or not, but only that this good life exists. However, he was deeply dissatisfied by this conclusion.

|

Then, over 30 years after the publication of Reasons and Persons he finally saw what he believed to be a fundamental mistake he had been making all of these years. In October 2016, he announced during a lecture in Oxford "I want to try and undo some of the damage I did" before setting out where he felt that he, and by extension many of the most eminent philosophers of the day, had been going wrong.

|

In the end, the problem seems almost trivial. Derek was convinced that it had been incorrect to say that my life’s being good only benefits me if it makes the world better for me, i.e. if it is better for me than my non-existence. Instead, my life might be good for me simply because it was good in absolute terms, even though it could not be said to be better or worse for me relative to non-existence. To put this another way, for more than 30 years he had been working on the problem of how to assign a value to my absence from the world for me. However, he now realized that one should not conflate the value of absence with the absence of value. The world in which I exist has value for me, the world in which I do not exist has no value for me. Hence, though it may not be ‘better' for me, my coming into existence can still be said to be ‘good for me'.

With this simple move, Derek concluded that we might escape this problem without implying the No-Difference View. This would not mean that that coming into existence with a good life was a benefit of the same kind as already existing and having our lives improved in some way (he thought it wasn’t), but we do have a way to coherently argue that good lives are good because they are good for the people living them. Derek wrote up his arguments into a lengthy paper ‘Future People, the Non-Identity Problem and Person Affecting Principles' which he submitted to the prestigious journal Philosophy and Public Affairs along with a note saying that the submitted draft was missing a conclusion and that he hoped to improve the article further with the aid of reviewer comments. The paper ended on a rather downbeat note, stating that while it resolved the Non-Identity problem, the principles it contained would still imply the Repugnant Conclusion. He was nevertheless consoled by the fact that these principles "would be only one of our beliefs" and that we might justifiably accept other principles that could yet avoid this conclusion.

Derek submitted the paper on January 1st, 2017 and sent copies of it to a few colleagues for their comments and feedback. Then, quite suddenly and without prior warning, he died. One of those colleagues says that the e-mail in which Derek had sent him this paper and the e-mail informing him of Derek's death sat one above the other when he opened his computer the following morning.

“There is another, better view” Stockholm (2014)

Derek Parfit was famously a fast and creative thinker. He used to advise students and colleagues to set up autocomplete shortcuts on MS Word for their most commonly used phrases to boost their productivity, unaware that very few other philosophers felt that their productivity was being restricted by their typing speed. Despite this, he published sparingly. He hated to commit himself to arguments unless he was certain of them. What he did produce however were numerous, and lengthy, drafts of papers and books (at least two of which never saw the light of day) that were widely circulated amongst the philosophical community and even more voluminous comments and responses to other philosophers on how they could improve their arguments. Likening Derek to an iceberg would be mistaken. Up to 10% of an iceberg is above the waterline, whereas I doubt if even 1% of Derek's work has ever been published. As one of his obituaries noted ‘When Derek Parfit published, it mattered!'

Thus, while Derek died before he could definitively set out how he thought we should avoid the Repugnant Conclusion; his thinking on the subject was already becoming clear.

In 2014, Derek was awarded the Rolf Schock Prize in Logic and Philosophy, perhaps the most prestigious award for philosophers and the closest thing we have to a Nobel Prize. As part of this, a symposium was held in his honour at the Swedish Academy of Sciences at which Derek gave a lecture. The organizers of that symposium insisted that the text of that lecture was published in the journal Theoria, and this gives us the only conclusive statement of Derek's final views about his Repugnant Conclusion.

In it, Derek asks us to imagine that ‘there would be no art, or science, no deep loves or friendships, no other achievements, such as that of bringing up our children well, and no morally good people', how could that be anything other than a moral tragedy, even if there was also ‘much more welfare in total?' Derek concluded that it could not. However, this did not mean we should abandon Utilitarianism, or Derek’s Simple View. Instead, he suggested ‘another, better view', we should accept utilitarian principles and other principles as well. Specifically, he believed that we should all accept the following claim ‘If many people exist who would all have some high quality of life, that would be better than the non-existence of any number of people whose lives, though worth living, would be, in certain ways, much less good.' Yet, was this not the view he had dismissed as crazy 30 years before?

The solution Parfit proposed was that art, science, love, friendship and the other ‘best things in life' must not be valuable simply because they were preferred by the people who enjoyed them, as Mill had proposed, but that they must be valuable in ways that other kinds of good thing are not. Controversially, it would follow from this that different values cannot always be measured on a single scale, either narrowly, in terms of pleasure and pain as Bentham had suggested, or even using the broadest possible conception of wellbeing, what makes someone's life good or bad for them.

Derek begins his argument for this conclusion at the relatively small scale:

“There can be fairly precise truths about the relative value of some things. One of two painful ordeals, for example, might be twice as bad as the other, by involving pain of the same intensity for twice as long. But in most important cases relative value does not depend only on any such single, measurable property. When two painful ordeals differ greatly in both their length and their intensity, there are no precise truths about whether, and by how much, one of these pains would be worse. There is no scale on which we could weigh the relative importance of intensity and length. Nor could five minutes of ecstasy be precisely 7.6 times better than ten hours of amusement.”

However, he believed that it had its fullest, and most profound, implications when applied athe the scale of of human history as a whole. When we consider such profound changes as the loss of science, art, love or friendship then this is not merely ‘roughly comparable' with a gain in the total quantity of wellbeing, but incomparability. As he argued, ‘This great qualitative loss would, I believe, make [this] in itself a worse world".

Amongst the many reasons why Derek was initially sceptical about this kind of philosophical move is that it might be elitist. If we argued that ‘the best things in life' were incomparably better than mere wellbeing would we not be lead to the conclusion that we should only really care about the best-off people, who actually enjoyed these things, and not about the great mass of humanity who did not? Furthermore, would we not be claiming that those things that happened to matter most to philosophers happen to be the most important things in life, and worthy of any amount of sacrifice by others to achieve. In the end, however, Derek concluded that this was not so, "if we care greatly about the quality of life, being in this sense perfectionists, that would not make us elitists, who care most about the well-being of the best-off people." Some may feel this is yet to be proven.

“What now matters most...” Globally (since 2009)

In fact, Derek Parfit cared deeply about the wellbeing of the worst off, and in particular about the alleviation of suffering. Along with a small group of other philosophers he helped to inspire the Effective Altruism movement, which encouraged people to do the most good that they can do, by thinking more about how they use their time, giving considerably more than they currently do to charity, and being more critical about the ultimate effects of their actions in the world.

Perhaps Derek's deepest held belief was that, contrary to much of popular opinion, there are objective facts about what we ought to do. This is what he meant when he talked about ‘reasons', and it was the recognition of these facts, either intellectually or merely by the application of common sense, that he saw as setting people apart. A cat cannot help its carnivorous ways, and it cannot help but follow its instincts to hunt and to kill, even if it no longer needs to. However, people understand that our actions can produce suffering. Once we become aware of this we seem to face a choice. Either we make a conscious attempt to dismiss this fact (animals don't really suffer, nothing we can do could reduce the amount of suffering in the world) or we feel we ought to change our behaviour, for instance by becoming vegetarian or giving money to charity.

One of Derek's driving passions, therefore, was the concern that legitimate disagreements about the nature of morality would disguise these facts and give people the impression that there were no moral truths. Scientists have disagreed about the ultimate nature of things for thousands of years, but few have doubted that they are studying the same empirical reality. Similarly, Derek argued, moral philosophers might disagree about the nature of morality, but they should all accept that they are ultimately searching for the same morality truth, ‘climbing the same mountain’ as he put it.

Disagreements about the value of future generations formed an essential part of this problem. However, they were by no means the most significant part. Hence Derek felt compelled to move further and further away from these issues as he explored the nature of disagreement in ethics (what we ought to do) and eventually meta-ethics (what it even means to say ‘what we ought to do'). However, ultimately, and unlike many of his contemporaries in these fields, Derek desperately wanted to make a difference in the world, and not only in moral philosophy. Hence, all his books ended with a peroration concerning what most needs doing, and the importance of doing it. Though he focused on moral philosophy to the exclusion of all else for much of his life, one shouldn’t overlook the fact that Derek did this because he was convinced that it was the most he could contribute to ensuring that what most needed doing was done.

Derek had hoped to write a 5th book, On What Matters Volume 4, in which he would present the theories that he had been working on concerning the ethics of future generations and in which he could finally achieve the goal he had set out to achieve back in 1968, of applying the principles of moral philosophy to real-world problems. He would never complete it. However, by inspiring others to work in Effective Altruism, and giving them sound arguments to support their convictions that people can, and should, do a lot more good than they currently do, this does not seem to matter so much. His work was, ultimately, worthwhile.

With this simple move, Derek concluded that we might escape this problem without implying the No-Difference View. This would not mean that that coming into existence with a good life was a benefit of the same kind as already existing and having our lives improved in some way (he thought it wasn’t), but we do have a way to coherently argue that good lives are good because they are good for the people living them. Derek wrote up his arguments into a lengthy paper ‘Future People, the Non-Identity Problem and Person Affecting Principles' which he submitted to the prestigious journal Philosophy and Public Affairs along with a note saying that the submitted draft was missing a conclusion and that he hoped to improve the article further with the aid of reviewer comments. The paper ended on a rather downbeat note, stating that while it resolved the Non-Identity problem, the principles it contained would still imply the Repugnant Conclusion. He was nevertheless consoled by the fact that these principles "would be only one of our beliefs" and that we might justifiably accept other principles that could yet avoid this conclusion.

Derek submitted the paper on January 1st, 2017 and sent copies of it to a few colleagues for their comments and feedback. Then, quite suddenly and without prior warning, he died. One of those colleagues says that the e-mail in which Derek had sent him this paper and the e-mail informing him of Derek's death sat one above the other when he opened his computer the following morning.

“There is another, better view” Stockholm (2014)

Derek Parfit was famously a fast and creative thinker. He used to advise students and colleagues to set up autocomplete shortcuts on MS Word for their most commonly used phrases to boost their productivity, unaware that very few other philosophers felt that their productivity was being restricted by their typing speed. Despite this, he published sparingly. He hated to commit himself to arguments unless he was certain of them. What he did produce however were numerous, and lengthy, drafts of papers and books (at least two of which never saw the light of day) that were widely circulated amongst the philosophical community and even more voluminous comments and responses to other philosophers on how they could improve their arguments. Likening Derek to an iceberg would be mistaken. Up to 10% of an iceberg is above the waterline, whereas I doubt if even 1% of Derek's work has ever been published. As one of his obituaries noted ‘When Derek Parfit published, it mattered!'

Thus, while Derek died before he could definitively set out how he thought we should avoid the Repugnant Conclusion; his thinking on the subject was already becoming clear.

In 2014, Derek was awarded the Rolf Schock Prize in Logic and Philosophy, perhaps the most prestigious award for philosophers and the closest thing we have to a Nobel Prize. As part of this, a symposium was held in his honour at the Swedish Academy of Sciences at which Derek gave a lecture. The organizers of that symposium insisted that the text of that lecture was published in the journal Theoria, and this gives us the only conclusive statement of Derek's final views about his Repugnant Conclusion.

In it, Derek asks us to imagine that ‘there would be no art, or science, no deep loves or friendships, no other achievements, such as that of bringing up our children well, and no morally good people', how could that be anything other than a moral tragedy, even if there was also ‘much more welfare in total?' Derek concluded that it could not. However, this did not mean we should abandon Utilitarianism, or Derek’s Simple View. Instead, he suggested ‘another, better view', we should accept utilitarian principles and other principles as well. Specifically, he believed that we should all accept the following claim ‘If many people exist who would all have some high quality of life, that would be better than the non-existence of any number of people whose lives, though worth living, would be, in certain ways, much less good.' Yet, was this not the view he had dismissed as crazy 30 years before?

The solution Parfit proposed was that art, science, love, friendship and the other ‘best things in life' must not be valuable simply because they were preferred by the people who enjoyed them, as Mill had proposed, but that they must be valuable in ways that other kinds of good thing are not. Controversially, it would follow from this that different values cannot always be measured on a single scale, either narrowly, in terms of pleasure and pain as Bentham had suggested, or even using the broadest possible conception of wellbeing, what makes someone's life good or bad for them.

Derek begins his argument for this conclusion at the relatively small scale:

“There can be fairly precise truths about the relative value of some things. One of two painful ordeals, for example, might be twice as bad as the other, by involving pain of the same intensity for twice as long. But in most important cases relative value does not depend only on any such single, measurable property. When two painful ordeals differ greatly in both their length and their intensity, there are no precise truths about whether, and by how much, one of these pains would be worse. There is no scale on which we could weigh the relative importance of intensity and length. Nor could five minutes of ecstasy be precisely 7.6 times better than ten hours of amusement.”

However, he believed that it had its fullest, and most profound, implications when applied athe the scale of of human history as a whole. When we consider such profound changes as the loss of science, art, love or friendship then this is not merely ‘roughly comparable' with a gain in the total quantity of wellbeing, but incomparability. As he argued, ‘This great qualitative loss would, I believe, make [this] in itself a worse world".

Amongst the many reasons why Derek was initially sceptical about this kind of philosophical move is that it might be elitist. If we argued that ‘the best things in life' were incomparably better than mere wellbeing would we not be lead to the conclusion that we should only really care about the best-off people, who actually enjoyed these things, and not about the great mass of humanity who did not? Furthermore, would we not be claiming that those things that happened to matter most to philosophers happen to be the most important things in life, and worthy of any amount of sacrifice by others to achieve. In the end, however, Derek concluded that this was not so, "if we care greatly about the quality of life, being in this sense perfectionists, that would not make us elitists, who care most about the well-being of the best-off people." Some may feel this is yet to be proven.

“What now matters most...” Globally (since 2009)

In fact, Derek Parfit cared deeply about the wellbeing of the worst off, and in particular about the alleviation of suffering. Along with a small group of other philosophers he helped to inspire the Effective Altruism movement, which encouraged people to do the most good that they can do, by thinking more about how they use their time, giving considerably more than they currently do to charity, and being more critical about the ultimate effects of their actions in the world.

Perhaps Derek's deepest held belief was that, contrary to much of popular opinion, there are objective facts about what we ought to do. This is what he meant when he talked about ‘reasons', and it was the recognition of these facts, either intellectually or merely by the application of common sense, that he saw as setting people apart. A cat cannot help its carnivorous ways, and it cannot help but follow its instincts to hunt and to kill, even if it no longer needs to. However, people understand that our actions can produce suffering. Once we become aware of this we seem to face a choice. Either we make a conscious attempt to dismiss this fact (animals don't really suffer, nothing we can do could reduce the amount of suffering in the world) or we feel we ought to change our behaviour, for instance by becoming vegetarian or giving money to charity.

One of Derek's driving passions, therefore, was the concern that legitimate disagreements about the nature of morality would disguise these facts and give people the impression that there were no moral truths. Scientists have disagreed about the ultimate nature of things for thousands of years, but few have doubted that they are studying the same empirical reality. Similarly, Derek argued, moral philosophers might disagree about the nature of morality, but they should all accept that they are ultimately searching for the same morality truth, ‘climbing the same mountain’ as he put it.

Disagreements about the value of future generations formed an essential part of this problem. However, they were by no means the most significant part. Hence Derek felt compelled to move further and further away from these issues as he explored the nature of disagreement in ethics (what we ought to do) and eventually meta-ethics (what it even means to say ‘what we ought to do'). However, ultimately, and unlike many of his contemporaries in these fields, Derek desperately wanted to make a difference in the world, and not only in moral philosophy. Hence, all his books ended with a peroration concerning what most needs doing, and the importance of doing it. Though he focused on moral philosophy to the exclusion of all else for much of his life, one shouldn’t overlook the fact that Derek did this because he was convinced that it was the most he could contribute to ensuring that what most needed doing was done.

Derek had hoped to write a 5th book, On What Matters Volume 4, in which he would present the theories that he had been working on concerning the ethics of future generations and in which he could finally achieve the goal he had set out to achieve back in 1968, of applying the principles of moral philosophy to real-world problems. He would never complete it. However, by inspiring others to work in Effective Altruism, and giving them sound arguments to support their convictions that people can, and should, do a lot more good than they currently do, this does not seem to matter so much. His work was, ultimately, worthwhile.

|

By the time that I, and indeed most people who worked with him, met Derek, the brilliant student of 1968 was hardly recognisable in the monomaniacal moral philosopher we knew. Yet in a way, and one in which Derek himself would have surely approved, it lived on as Derek supplied what he felt he was best at, good philosophical arguments, to a community that was able to achieve what he alone could not.

“What now matters most” Derek argued on the final page of his final book, published a few weeks after his death “is how we respond to various risks to the survival of humanity.” |

However, in line with his controversial views about the value of future generations, Derek did not simply take the line, suggested by other philosophers, that that badness of human extinction lay solely in the many future people who would no longer come into existence, most of whom would have lives worth living. Rather he saw the real tragedy in human extinction as something greater:

“Life can be wonderful as well as terrible, and we shall increasingly have the power to make life good. Since human history may be only just beginning, we can expect that future humans, or supra-humans, may achieve some great goods that we cannot now even imagine … Some of our successors might live lives and create worlds that, though failing to justify past suffering, would have given us all, including those who suffered most, reasons to be glad that the Universe exists.”

Arguments about the Repugnant Conclusion have not ceased because Derek Parfit is no longer here to contribute to them, and it seems unlikely that everyone will accept his solutions to the problems they raise. However, what mattered to Derek was not just getting moral philosophers to agree, but ensuring that their arguments could help us to understand the reasons we have to do what needs doing, to ensure the survival of humanity, reduce global poverty and fulfil our potential as a species, and, through this understanding, lead us to achieve these goals.

[Many details about Derek’s life here were taken or confirmed via the videos from the celebration of his life held at All Souls College in June 2017, all of which are freely available to view at https://vimeopro.com/user16707643/celebration-of-derek-parfit?. Prior to publishing it I shared this biography with several friends and colleagues who provided useful feedback and suggestions. Unfortunately I didn’t keep a record of who these were as at the time I did not have any clear intention to ever make it public, nevertheless, I am grateful to all of them. Thanks also to Sam Enright for correcting some typos in my origional posting. If you would like to contact me about this article or any other aspect of my work please don't hesitate to e-mail sjb316 (at) cam.ac.uk

“Life can be wonderful as well as terrible, and we shall increasingly have the power to make life good. Since human history may be only just beginning, we can expect that future humans, or supra-humans, may achieve some great goods that we cannot now even imagine … Some of our successors might live lives and create worlds that, though failing to justify past suffering, would have given us all, including those who suffered most, reasons to be glad that the Universe exists.”